An odd thing about being a being in the universe is that there is apparently nothing fixed, necessary, or ultimate about one’s form of being. Humanity will come and go. We will continue to build technologies that alter our manner of experiencing the world. What being is like for you and I in the here and now is apparently but one tiny and arbitrary corner of a vast space of possible modes of existence.

For me, adopting this reference frame creates a degree of tension when I consider that A) certain important meaning-structures in my life are tightly coupled to aspects of my form of being which may be quite arbitrary; yet B) at a spiritual level, I tend to relate to these meaning structures as if they are a deep and fundamental aspect of being itself.

All of this leads me to ponder: Are these meaning-structures indeed arbitrary constructions that I can or should seek to transcend? Or can they actually transcend great swaths of possibility space? Or is this a false dichotomy?: Is meaning which squeezes itself into small, obscure corners of possibility space the only meaning that there is (and this is fine)?

Let’s take love as a case study in order to make these questions more concrete. Love is unquestionably rooted in biology, and our animal biology may indeed exist in some narrow, arbitrary corner of possibility space.1 Moreover, many details about this narrow biological story—like the fact that concealed ovulation plays an enormous role in determining the non-trivial shape of human relationships—feel brutal and zero-sum. Yet, as a biologically male modern adult human, I relate to the idea of love as something fundamental, inescapable, and even ultimate—something which undergirds, animates, and motivates much of the meaning-structure in my life.2 3

This blog post is my response to this tension in the form of an exploration of the phenomenological nature of love. There may be other ways to defend love’s central role in our meaning-making—arguments of emergent teleology in the universe which manifests in convergent biological forms. But in adopting the phenomenological lens, I want to go a layer deeper, and argue that some aspects of love are fundamental to the conscious experience of any being that is embedded within reality. Stated more carefully, the aim is to clarify exactly what is at stake in love, phenomenologically: If I were to forsake love, what elements of my experience would be difficult or impossible to recover?

As this will be a post about the phenomenology of love, we’ll start with an opinionated amateur’s introduction to the topic.

Phenomenology is the “meta-awareness” practice of noticing patterns and features of conscious experience. The primary fruit of this practice is an alteration of our mind (learning) which we experiences as new tendencies of thought and which structurally we can describe as the development of new mental models. A secondary fruit of this practice is the re-representations of these mental models which we construct for ourselves and others via language or other modalities.

In some sense, because all of the abstractions that normally go into any kind of modeling activity are mental phenomena, it follows that all modeling is in some sense phenomenology. But when we engage in phenomenology, we aspire to unpackage and unbundle our abstractions until the thing that we are abstracting is less “other abstractions” and more “basic, raw experience.” As all of modeling is reductive in nature, so is phenomenology.

Here is a reductive phenomenological question which I might ask you at a dinner party:

What is the dimensionality of experience?

This question slips in a funny assumption which is that mental states live in what is called a “vector space.” This would mean that you could take any two mental states and “blend” them together to get a third mental state representing a combination of the first two. The question then asks what is the size of the minimal collection of mental states such that any other mental state can be created from a linear combination of these states.

It seems pretty natural to think of certain domains of experience this way—e.g., the dimensionality of visual experience should be something like 3 (dimensionality of color space) times the number of spatial dimensions (pixels). But what about other components of our mental state, like our emotions?

What is the dimensionality of emotion?

What does it feel like to be annoyed? How much overlap is there being this feeling and the feeling of being confused? Or the feeling of being angry? Afraid? As a thematically similar question, I’ve recently become curious about how much of the experience of these mental states can be described in terms of expectations.4

This notion came to me when I did indeed pose the question of feeling-space-dimensionality to a group of unsuspecting coworkers at a company dinner, after I had been reading about something called “Active Inference.” Active Inference is a model of cognition which posits that the activity of a living system can be fully captured by free energy minimization framework in which the free energy term corresponds roughly to prediction error. So living systems such as human minds function by minimizing prediction error.

Active inference literature tends to use the terminology of prediction, but I’ve found that “expectation” is often the better word to describe the associated experience for humans. We don’t just predict things. It’s deeper: we expect them. When our predictions, so labeled, fail to come about, we may suffer a degree of embarrassment or frustration. But when we call something a prediction, the context is usually one in which we are explicitly acknowledging and even hedging against the uncertainties involved. When we expect something, we have written off the uncertainties to some degree and we are willing to use our prediction as a foundation for planning (expectation chaining) and action.

Expectation has it’s own phenomenology, which is closely related to imagining. We could easily devote an entire blog post to the phenomenology of imaginal flows. In what follows, it may be helpful to try interchanging the terms expectation and imagination.

Let’s see what happens when we try to map common emotional states to states of our expectations. Here’s a cursory mapping:

- Fear: Expectation of something acutely bad

- Desire: Expectation of something acutely good, but contingent; expecting that desired thing leads to something good

- Happiness: Expectation of generally good things, absence of unsatisfied expectations

- Sadness: A relinquishing of cherished expectations; seeing such expectations systematically thwarted

- Confusion: Ongoing discrepancy between expectation and observation

- Annoyance: Obstruction of an expectation or desire in petty or immediate ways

- Curiosity: High entropy in expectations. I don’t know what to expect, but the range of expectations is not threatening

- Boredom: Degeneracy of expectations. I know exactly what to expect

Note, as an aside, that I’ve freely used value-oriented language like good and bad here, which begs for further investigation. Again, if we use active inference as a guide, we can try to make the description self-contained in terms of expectations.

The active inference framework avoids explicitly attributing values to states by inverting the normal mental model of planning and action (e.g. from reinforcement learning). A succinct way to put this might be that instead of our hopes and expectations deriving from the way that we value different states of the world, it is rather our hopes and expectations that determine and prefigure what it is that we value. Active interference literature will commonly make perplexing claims to the effect that an organism will predict a “desired” state for itself and then try to minimize the error of this prediction.

While this framework can be counterintuitive, I personally find that it stands up fairly well to introspection: One of the ways in which I know that I want something, phenomenologically, is that I find myself imagining it, daydreaming about it, planning for it, expecting it—all close cousins, phenomenologically speaking.

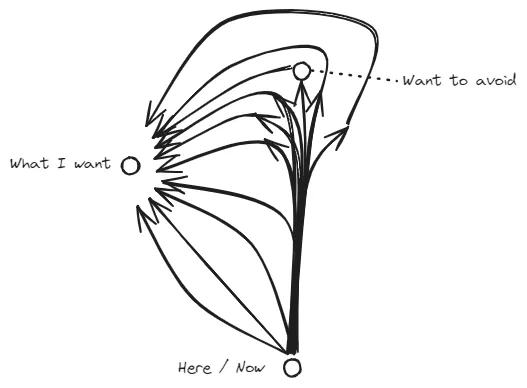

I think it’s compelling to think of “good” states as those which are “sinks” of imaginal flows (those toward which our imaginings and plannings tend to converge) and “bad” states as those which are “sources” of imaginal flows (we never plan toward this state, only away from it).

With this aside out of the way, let us recap: We’ve seen that there is arguably some interesting connection between an emotional state and an orientation of expectations. We could continue down this path by asking further questions: What is the phenomenology of expectation? When we say that we are angry, are we primarily saying something about the state of our expectations or are we primarily communicating an inferential judgement about the state of our nervous system based on experiences like the clenching of our muscles and the fact that we have a tendency to shout? Is the second of these still, phenomenologically, just a form of expectation? Et cetera.

For now, I’m content to note that, at the very least, the language of expectation seems to capture something important and fundamental about many of our mental/emotional states. I particularly like this way of thinking about feelings and emotions because it grounds them in the context of broader life trajectories and complexities therein. How I feel emotionally depends very strongly on how my life is going relative to how I want it to go. I want to use this connection to further explore the phenomenology of love.

Let’s ponder some different situations in life and what they feel like in terms of expectations.

I’m stuck. I’m depressed. My expectations chain together and loops, never getting me closer to where I want to be.

I’m compromising. I’m lying. My expectations bifurcate between different possible sides of a zero-sum equation. I have no peace.

I’m learning. My expanding the set of situations in which I can have well-defined expectations.

I’m developing and growing. I’m expanding my awareness in ways that allow for different expectations than what I was stuck with previously.

Something (an idea, a model, a story) is beautiful. It is intelligible. It helps me to make sense of complexity, i.e., make predictions in complex situations.

I’m delighted by something. It meets or exceeds my highest expectations. It catalyzes my learning. It helps me to grow and develop. It is beautiful.

Please add your own. What do different situations feel like to you? Does the language of expectation do a good job of capturing this feeling?

In the final part of this post, I want to explore how this phenomenological picture can be applied to loving relationships. The motivating question, once again, is something like, “Why might having pleasurable relationships be an essential activity of all conscious beings, rather than an incidental result of something like biological evolution?"

I’m thinking about the way that my expectations should flow relative to someone that I love.

- I expect that they will surprise me; they will act and respond in ways that I cannot fully predict.

- I expect that they will help me to grow, develop, and learn, and that they will grow with me. When we individually or jointly come across dilemmas (expectations which are kinked or knotted), they might offer a different perspective.

- When I have an idea (an expectation about how the world will work), they will debias that idea by forming their own expectations, which I trust (expect them to be rigorous and valuable).

All of these patterns give rise to the feeling which I have described as delight. The heart of the story here seems to be that this overarching experience of delight is born from a way in which conscious beings can complement each other. I am prone to love someone who can act almost as an extension to myself. They are similar to me enough to be intelligible so that I can trust them. But different enough so that together we do not degenerate into something no more powerful than either one of us alone.

There is clearly an interesting narrative here around the idea that my own limitations create the conditions under which this whole arrangement of expectations and feelings (love) can emerge. 5 We have argued here that love is not just peculiar to the locally emergent phenomenon of sexual biology. Some form of love might extend to all conscious beings which exist in complementary relationships—which could very well be the set of all beings: perhaps there are fundamental bottlenecks in the structure of intelligent things which enforce limitations on the capacity of an individual awareness, ensuring that consciousness will be separated/partitioned/individuated into smaller, complementary units. Perhaps love is, indeed, fully transcendent across space, time, and possibility…

I think that a shortcoming of this whole exploration is that it doesn’t fully allow me to answer irksome questions about love in the age of AI. How does/should my belief that the object of my love is also conscious impact the quality of my experience? Can I feel the same delight in another with and without a theory of mind that feels approximately valid? Perhaps these are questions for a follow-up.

In closing, I want to ask: All in all, do you find this account of love compelling? And further: Why do you need a compelling account of love? Why do I need one? The reason that I need for both of us to have a compelling account of love is simple: because I want love to feel inevitable, unavoidable, quintessential to existence… because I want to seduce you… because I want to have sex with you. Obviously.

-

There’s perhaps more to say here around themes of convergent evolutionary emergence, but we won’t deeply get into biological discussions here. ↩︎

-

I’m not being too particular about my criteria for something to be meaningful. I think that a meaningful story of love must both “make sense” and concord with the ways that we like to view ourselves in the context of love. I like to think of love as partaking in something transcendent. Narrow versions of the biological story don’t allow me to do this. ↩︎

-

I’m not sure whether this is a discrepancy which I have previously failed to notice, or whether it is one where I have tacitly assumed that there was probably some reasonable resolution. Over the years, I think that I’ve come to recognize the experience of being complicit in some form of group think and then coming into contact with a person who implicitly challenges the group’s framing and assumptions. It always goes something like “Ok, this person doesn’t quite get it. What are they missing? Ohhh, shiiit.” I recently found myself in this awkward position during a conversation with someone whose default way of relating to love was more or less as a biological absurdity. The fact that here was a person who was capable of adopting this way of relating to love caused me to question what never before felt questionable: Is love merely a grand lie, a mostly vacuous cultural meme which lives in the service of a more brutish biological reality? ↩︎

-

It’s clear that many of these emotional states also have a physical manifestation within our bodies which we can feel; I’ll focus less on this element ↩︎

-

In this sense, this entire article starts to look like an extension of a previous meditation on faculties that emerge from limitations ↩︎